Table of Contents

1. What Is Ceramic Machining?

Ceramic machining refers to the manufacturing process of removing material from ceramic surfaces through milling, drilling, grinding, turning, and other methods to achieve final design dimensions, tolerances, and surface quality.

Ceramic machining can be divided into two major stages:

① Green Machining

Processing performed before ceramic sintering

Material is not fully hardened, allowing use of conventional cutting tools

High machining efficiency, but dimensions shrink during sintering

② Fully-Dense Machining

Processing performed after ceramic sintering achieves full density

Material exhibits extreme hardness and high brittleness

Diamond tools are mandatory

Enables precision tolerances and final surface quality

Ceramics possess characteristics of high hardness, low density, high brittleness, high-temperature resistance, and chemical corrosion resistance. These properties make them superior engineering materials while simultaneously increasing machining difficulty.

2. Why is Mechanical Processing Necessary for Ceramics?

For fired ceramics, machining is required to achieve precise tolerances that cannot be met during the green ceramic processing stage. While green ceramics can meet some tolerances, aspects like bore diameter and surface finish typically require additional machining after firing.

For instance, specialized functionalities in ceramic tubes and rods cannot be incorporated during the green stage and necessitate post-firing machining. Sintering, a critical phase in ceramic production, hardens the material but also induces shrinkage and warpage. These issues frequently require corrective machining to achieve the desired tolerances. Furthermore, ceramic components, particularly those for technical applications—may feature intricate and complex design elements that can only be created through post-sintering machining.

3. What are the Methods for Machining Ceramics?

Ceramic production yields parts, products, and components varying in size, shape, and strength. Machining represents the largest cost in ceramic manufacturing, accounting for 50% to 90% of a part’s total cost. The efficiency of ceramic machining is evaluated by material removal rate (MRR), which measures the amount of material removed from the surface per minute. Two types of machining exist, each tailored to the specific requirements of the ceramic being processed. Machining dense ceramics demands more robust and durable tools compared to those used for green ceramics. Additionally, the timing of the machining process differs: green ceramics are machined before full hardening, while dense ceramics undergo machining as the final step in the manufacturing process.

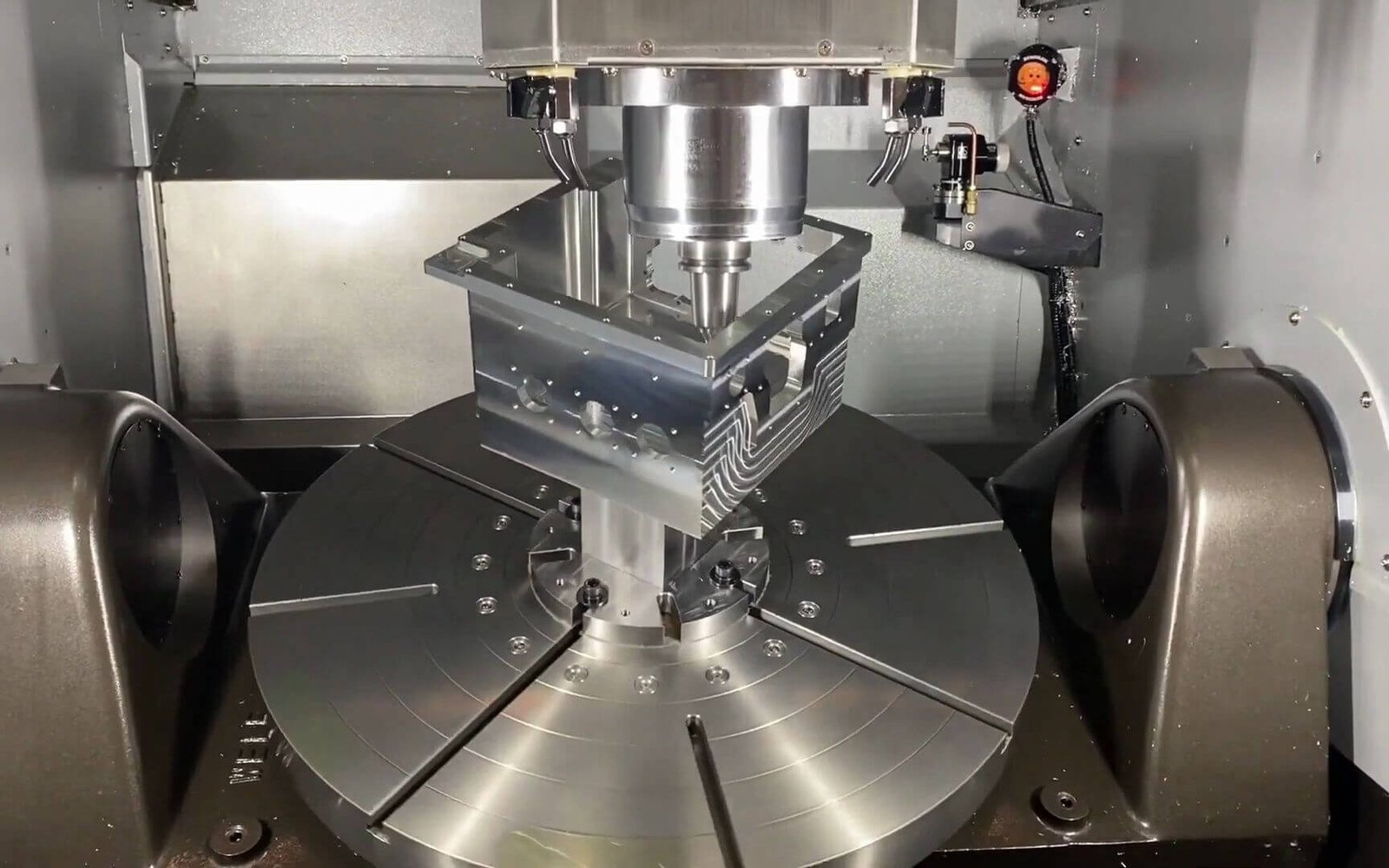

Abrasive Machining

Abrasive machining can replace large-chip machining techniques such as milling, planing, broaching, and turning. Compared to these traditional methods, it delivers superior surface quality and precision while producing minimal burrs. Abrasive machining is particularly effective for difficult-to-machine materials like dense ceramics.

Grinding encompasses multiple methods, including reciprocating, internal, external, centerless, and creep feed grinding. This process uses a rotating grinding wheel to remove material from the workpiece surface. The grinding zone is continuously flushed with coolant to cool and lubricate the contact area. As coolant flows through the grinding zone, it aids in removing the fine chips and debris generated during grinding. Grinding materials for ceramics include diamond and cubic boron nitride (CBN), each available in different grit sizes. Diamond is often preferred for its hardness, though it wears faster than CBN. CBN, while less hard than diamond, tends to be more durable. Both materials are embedded in resin to enhance their effectiveness.

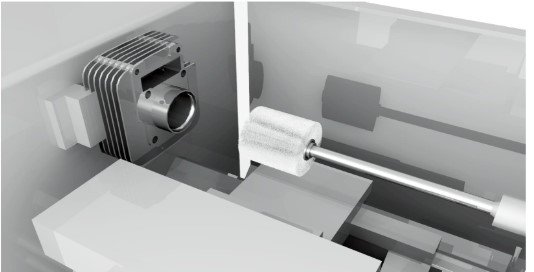

Honing Process

Honing employs stationary abrasives, with diamond being the preferred choice for ceramics. Unlike grinding, honing operates at slower speeds. It is primarily used to correct dimensional tolerances and is most commonly applied to polish internal cylindrical surfaces, such as the cylinder walls in automotive engines.

Such applications can be fully automated, enabling complete control over every step of the process, including automatic part dimension measurement. Honing is also used for finishing external surfaces, such as the outer surfaces of ball and roller bearing races, valves, and gear teeth. Because honing operates at lower speeds, it generates less heat compared to grinding, thereby minimizing damage and deformation to the workpiece caused by heating. This reduced heat also lowers cooling requirements, although chemicals are still necessary to maintain adequate lubrication. Unlike grinding, there has been little effort to develop honing fluids specifically for advanced ceramics.

Ultrasonic Machining Process

Applications such as these can be fully automated, enabling complete control over every step of the process, including automatic part dimension measurement. Honing is also used for finishing external surfaces, such as the outer surfaces of ball and roller bearing races, valves, and gear teeth. Since honing operates at lower speeds, it generates less heat compared to grinding, thereby minimizing damage and deformation to the workpiece caused by heating. This reduced heat also lowers cooling requirements, though chemicals remain necessary to maintain adequate lubricity.

Unlike grinding, little effort has been made to develop honing fluids specifically for advanced ceramics. Vibration reduces friction, helps limit fluid ingress, and aids chip removal, ultimately increasing machining speeds. Tool diameters typically reach up to 50 mm. In rotary ultrasonic machining, small grinding and thread-cutting wheels, along with core drills and solid drills, are commonly employed. In this process, it is crucial to consider the effects of cutting fluids, bonding, abrasive properties, and grinding parameters.

Therefore, improvements in ceramic grinding technology should be applicable to rotary ultrasonic machining. In ultrasonic impact machining, the tool itself does not contain abrasives or make direct contact with the workpiece. Instead, this technique employs an abrasive slurry circulating between the vibrating tool and the workpiece. The tool vibrates the liquid and abrasive particles, which then impact the workpiece, causing indentations and fractures that result in material removal. The distance between the workpiece and the vibrating tool significantly affects removal rates. Ultrasonic impact grinding is a widely used method for machining advanced ceramics, second only to grinding. Increased vibration frequency and specialized fluids can enhance machining speeds in ultrasonic impact grinding.

Grinding and Polishing Processes

Grinding, like honing, is primarily a finishing process applied to objects machined close to their final dimensions. However, unlike honing, grinding employs a loose or free abrasive method. During grinding, the workpiece is pressed against a rigid surface, typically cast iron coated with an abrasive particle slurry. Some particles embed into the grinding tool’s surface and cut into the workpiece, while others roll between the two surfaces, aiding material removal.

Grinding and polishing are sometimes considered distinct processes, though this is not always accurate. Grinding employs rigid, solid surfaces to achieve precise tolerances, eliminate damage, and enhance surface smoothness. Polishing, on the other hand, utilizes softer, more flexible surfaces primarily to repair damage and produce exceptionally smooth finishes.

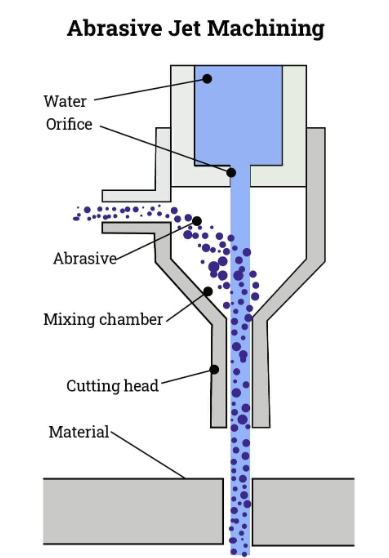

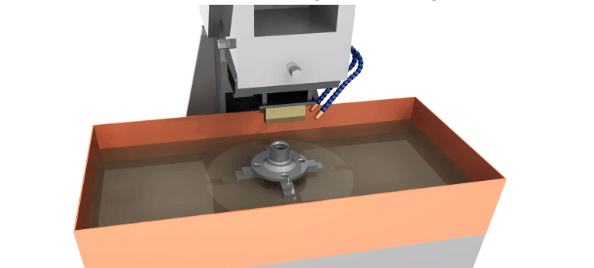

Liquid Abrasive Jet Cutting Process

Liquid jet systems are primarily used for cutting rather than forming or surface treatment. This technology is frequently employed on porous materials, which can be cut at very high rates. However, due to hardness and density considerations, liquid jet cutting performs poorly on advanced ceramics, resulting in significantly reduced cutting rates. The incorporation of abrasive particles into the fluid stream has facilitated the application of liquid jet cutting on modern ceramics. This technique combines localized cavitation-induced fractures with slurry erosion to remove material. However, adding abrasive particles can cause various types of machine damage. Consequently, the liquid abrasive jet process is unsuitable for components requiring precise tolerances and high surface quality.

Non-Abrasive Machining

Some non-abrasive machining methods include:

Electrical Discharge Machining (EDM)

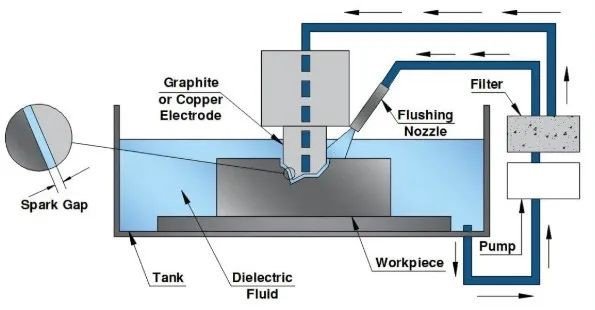

Electrical energy can also be used for ceramic machining. This is known as Electrical Discharge Machining (EDM), which has found numerous applications in advanced ceramic machining over the past few years. EDM requires the resistivity of ceramic workpieces to be less than 100Ω-cm. This means EDM cannot be used to machine glass and certain ceramics.

EDM has been proven effective for materials such as silicon-infiltrated silicon carbide, siliconized silicon carbide, and hot-pressed silicon carbide. To extend EDM’s applicability to other ceramics, its resistivity must be reduced to the desired range. However, it remains uncertain whether EDM constitutes a low-damage machining method, as it typically leaves a surface layer of melted or heat-affected material containing high residual stresses and numerous microcracks.

Laser Beam Cutting

Focused laser beams are widely used for precise cutting of various materials, including metals, wood, and ceramics. Innovative methods have been developed, such as intersecting two laser beams within a workpiece to cut blind seams. This technique employs specific cutting geometries, particularly when removing certain sections of the workpiece is required.

Friction Cutting and Microwave Cutting Processes

Friction cutting involves using circular blades whose rotational speed generates more heat than the material being cut. In this process, materials like aluminum oxide and silicon nitride are grooved by rotating low-carbon steel discs, followed by water cooling. Conversely, microwave cutting involves locally heating sintered alumina with microwaves. When penetrating sintered alumina wafers, this technique causes localized melting and explosive ejection of molten material from beneath the surface. While effective for cutting and slicing tasks, these methods are generally unsuitable for creating contour surfaces with tight tolerances.

Combined Methods

Some combined approaches include:

Thermally Assisted Turning Process

Certain engineering ceramics reportedly perform well when heated with a plasma torch during rotation. This technique heats the workpiece material to up to 1000°C before cutting with polycrystalline diamond composite (PDC) or CBN cutting tools. The enhanced machinability arises from the transformation of the material from a harder to a more plastic state at elevated temperatures due to deformation and removal processes. Although tool wear was reduced by a factor of 8 when turning silicon nitride, wear levels remained excessively high. Heating thermally sensitive materials like alumina and zirconia with a plasma torch did not significantly improve machinability. Engineers can enhance ceramic ductility by first laser-heating the material before cutting with diamond tools. However, thermal-assisted turning remains unsuitable for high-volume production due to limited tool life and insufficient surface finish.

Mechanical-Electrical Discharge Machining

Recent advances have enabled the integration of electrical discharge machining with ultrasonic processing techniques. Through extensive experimentation, engineers have determined how to effectively machine titanium diboride using metal-bonded diamond tools. Under specific conditions, this method achieves higher material removal rates and a removal ratio of 110 (workpiece loss to wheel loss). However, further research is needed to assess whether this technology can be applied to other EDM materials with sufficient electrical conductivity.

Consequences of Improper or Inadequate Ceramic Machining

Despite ceramic materials’ strength, hardness, and other beneficial properties, improper machining can compromise their integrity and introduce defects. Issues such as uneven cuts or irregular, distorted edges can affect ceramic rigidity. Machining aims to refine ceramic components to meet precise tolerances and design specifications. Even minor oversights during this process can lead to significant failures.

Ceramic tubes may appear as minor components within mechanisms, yet failure to machine them to precise dimensions can cause substantial damage and safety hazards. This principle also applies to geometries requiring machining to exact tolerances for proper integration into finished designs. A critical aspect of machining involves addressing errors or defects arising during the firing process, such as shrinkage and warping.

The machining process corrects and eliminates these flaws to ensure ceramic parts meet required tolerances. To achieve optimal results and guarantee final product quality, machining must be performed with the highest precision. The most critical failure in ceramic machining is the development of microcracks and fractures, often caused by improper tool usage or inappropriate tool selection. Ceramics are highly brittle and extremely susceptible to crack damage. Given the prevalence of this issue in ceramic manufacturing, producers typically employ intense light or piezoelectric inspection methods to meticulously and thoroughly examine finished products.

4. Advantages And Disadvantages Ceramics in Ceramic Processing

This chapter will discuss the applications, advantages, and disadvantages of ceramics used in ceramic processing.

Advantages of Ceramics in Ceramic Processing

• Due to their extremely high hardness, they are frequently used as cutting tools and grinding powders.

• Their high melting points make them highly suitable as refractory materials.

• They also serve as effective thermal insulators, another reason for their use as refractories.

• Their high electrical resistance makes them excellent insulators.

• Their low mass density enables the production of lightweight ceramic components.

• They are generally corrosion-resistant due to oxidation resulting from their unique chemical bonding structure.

• They are cost-effective because they are readily available.

• Glazed ceramic materials are durable and stain-resistant.

Disadvantages of Ceramics in Ceramic Processing

• They are not particularly elastic.

• They lack significant tensile strength.

• Strength varies widely even among similar specimens.

• Their creation and shaping are challenging.

• Maintaining dimensional tolerances throughout processing is difficult.

• Ceramic products have poor shock resistance, causing them to fracture upon impact.

• They possess a low coefficient of friction, allowing other materials to slide easily.

5. Applications of Engineering Ceramics

Engineering ceramics are indispensable in industries that demand high precision, durability, and performance under extreme conditions. Their unique combination of hardness, thermal stability, chemical resistance, and electrical insulation makes them ideal for a wide range of applications.

Aerospace

- Silicon Nitride Bearings: Offer exceptional wear resistance and low friction for high-speed rotating components, essential in jet engines and aircraft turbines.

- High-Temperature Resistant Insulators: Ensure electrical stability in extreme temperatures, used in avionics and high-power aerospace systems.

- Nozzles and Jet Orifices: Maintain shape integrity under thermal shock and erosive environments, critical for fuel injection and propulsion systems.

Medical Devices

- Zirconia Dental Implants: Biocompatible and highly durable, providing long-lasting dental solutions with superior strength.

- Ceramic Surgical Instruments: Resistant to corrosion and wear, maintaining precision in minimally invasive surgeries.

- Bioceramic Joint Ball Heads: Used in orthopedic implants for hip and knee replacements, offering excellent wear resistance and low friction.

Semiconductors & Electronics

- Ceramic Substrates (AlN, Al₂O₃): Provide high thermal conductivity and electrical insulation, supporting advanced semiconductor devices and power modules.

- Spacer Rings and Tooling Fixtures: Ensure precise assembly and stability in manufacturing electronic components.

- Electronic Packaging Materials: Protect sensitive circuits from heat and mechanical stress, improving device reliability.

New Energy (Lithium Batteries / Hydrogen Energy)

- Zirconia Oxygen Sensors: Critical for monitoring oxygen levels in fuel cells and battery management systems.

- Ceramic Electrical Insulating Supports: Provide high-temperature stability and electrical insulation in energy storage and hydrogen applications.

- Ceramic Valve Cores: Durable and wear-resistant, essential for controlling fluid or gas flow in energy systems.

Industrial Equipment & Machinery

- Ceramic Sealing Rings: Resist wear and chemical corrosion, extending equipment life in pumps, compressors, and valves.

- Valve Seats and Nozzles: Maintain precision under high pressure and abrasive conditions.

- Wear-Resistant Guide Rails: Ensure smooth operation in heavy machinery and automated production lines.

Consumer Electronics

- Ceramic Enclosures: Provide scratch resistance and aesthetic appeal for smartphones, tablets, and wearable devices.

- Wear-Resistant Components: Extend the lifespan of high-friction parts in devices like cameras and home appliances.

- Camera Structural Parts: Maintain dimensional stability and precision in compact optical assemblies.

6. Challenges in Machining Ceramics

Due to the inherent properties of ceramics, machining them presents several challenges. Their high hardness, brittleness, and resistance to machining make the process difficult. Traditional machining techniques often fail because they rely on forming chips through shearing, which causes the brittle structure of ceramics to fracture. Machining ceramics is a precise process requiring careful control, attention to detail, and skilled craftsmanship. Many manufacturers now favor CNC machining of ceramics to overcome challenges associated with manual techniques. The brittleness of ceramic materials can cause microcracks and fractures during machining, resulting in defective products. Machining ceramics may lead to surface damage, edge chipping, and pitting. To ensure dimensional accuracy and minimize collateral damage such as surface cracks, the machining process requires careful monitoring.

7. Conclusion

Ceramic materials, mixed, formed, and molded, are used to manufacture industrial and commercial parts and components. Machining plays a critical role in their production by enhancing the properties and tolerances of ceramic products. Similar to machining metal parts, ceramic machining involves removing portions of the surface to alter the size and shape of ceramic components. Unlike metalworking, ceramics require specialized tools capable of matching their hardness, strength, and toughness. Due to their density and hardness, ceramics necessitate extensive and precise machining processes, including drilling, turning, grinding, and milling.